Early Dynastic 3000–2350

The Flood

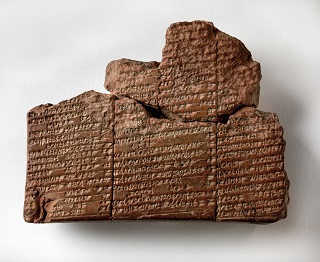

At the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period, about 2900 BC, a great flood swept over Sumer. The Euphrates and Tigris rivers overflowed their banks and forced the Sumerians to abandon their cities and fields – fleeing for their lives. While it was common for the rivers to flood this was a massive flood which disrupted all of Sumer. Many accounts of this flood exist today, the earliest accounting was written by the Sumerians and is referred to as the Eridu Genesis. In this version, the hero of the story is the Priest-King of the Sumerian city of Suruppak. He is called Ziudsura (‘life of long days’) and he is chosen by God (Enki) to survive the flood and preserve life and knowledge on Earth. Found in the Sumerian city of Nippur the tablet dates to about 1600 BC but the style of the cuneiform script dates it’s origin to about 2300 BC; it is the oldest known version of the Great Flood. This Sumerian version of the story of the flood is fragmentary; missing two thirds of the story. However, the story line can easily be filled in by later versions.

This is an extract from the oldest version we have of the Flood (Eridu Genesis) and is translated by Thorkild Jacobson. Portions are missing due to the fragmentary state of the tablet so a general story line, as told by later versions, has been inserted as needed. A full translation, which includes the creation of the black headed people, can be read at the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (ETCSL).

|

(Missing part: Mankind has been making so much noise, disturbing the sleep of the gods, that Enlil persuades the other Gods to destroy mankind.) That day, Nintur wept over her creatures At that time Ziusudra was king and lustration priest. *Note: here Enki warns Ziusudra of the impending flood (Missing part: Enki tells Ziusudra to build the ark and load it with pairs of animals.) * Note: The Flood occurs *Note: The Sun God Utu enters the boat and Ziusudra makes a sacrifice (Missing part: Enlil is angry at Utnapishtim surviving the flood but Enki calms him down) “You here have sworn by the life’s breath of heaven, the life’s breath of earth that he verily is allied with you yourself; you there, An and Enlil, have sworn by the life’s breath of heaven, the life’s breath of earth, that he is allies with all of you. He will disembark the small animals that come up from the earth!” Note: Ziusudra is granted eternal life and made preserver of animals and man |

While this version of the Flood myth may seem primitive keep in mind that it is the oldest version and writing was still evolving. The more recent and complete versions of the legend tell the same story with far greater detail and the names have been changed to reflect the time and culture of the authors.

The Ziudsura figure appears as Atrahasis (‘exceedingly wise’) in a Babylonian version written about 1750 BC.

The most complete version of The Flood is included in the Epic Of Gilgamesh written about 1100 BC by the Babylonians; this version is based upon five far older Sumerian poems all laced together to form a complete story. The Flood part of the epic is tablet 11 out of a 12 tablet story and the hero figure is Utnapishtim (‘he found life’). The Epic of Gilgamesh is a story about a Sumerian King of Uruk, who may have lived about 2700 BC, and the epic is considered the oldest and greatest epic ever written – our Babylonian copy predates the ‘ancient’ Greek Iliad and Odyssey by 400 years and the core material, the five Sumerian poems, predate the Iliad and Odyssey by nearly 2000 years!

By the time of the fourth known version of the story, which we know as Noah and the Flood, writing had developed to the point of being able to convey complex ideas and as every storyteller knows a story becomes better every time you tell it! The Hebrews likely wrote their version about 586 BC during the Babylonian Captivity.

Sumerian King’s List

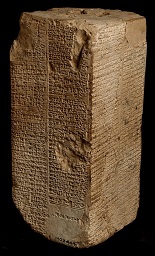

The archaeologists sought to construct a historical timeline for Sumer – a linear listing of the Kings and their reigns. Some 20 different tablets have been recovered all containing similar accounts while at the same time varying in the details, they are called the Sumerian King’s List. While these tablets must have based upon some earlier tablets it is clear that they were rewritten in order to legitimize the reign of the particular King who copied it. All these versions of the King’s List date to the Old Babylonian period about 1800 BC, except one. This older version states that it was copied from an earlier tablet during the reign of the Sumerian King Shulgi of Urim who reigned about 2093 BC. The Sumerians referred to it as Nam-Lugal (Kingship) after its incipit or opening words of the text.

cuneiform dedication by King Shulgi

(2094-2047 BC) to the goddess Inanna.

There are two major differences between Shulgi’s King List and all the other copies. The first is that Shulgi’s list is an actual Sumerian King describing Sumerian history while all the other copies date 300 years later from a Babylonian point of view. The second main difference is that the Sumerian version does not mention the flood while the Babylonian versions start long before the flood and uses the flood as a dividing line in the tablet; Kings reigning before the flood and those after the flood.

One version of the King’s List is used as the standard simply because it is nearly intact. The Weld-Blundell prism is a clay ‘prism’ about 8 inches high and 3.5 inches per side and each side has two columns of cuneiform written in Sumerian. The prism was likely written during the final years of the Babylonian King Sin-magir (1827–1817 BC.)

The Weld-Blundell prism reads:

|

After the kingship descended from heaven, the kingship was in Eridug. In Eridug, Alulim became king; he ruled for 28800 years. After the flood had swept over, |

There are problems with the ‘before the flood’ portion of the text. Namely the impossibly long spans of time and that none of the listed kings listed are known to have ruled. One of the listed kings, Dumuzid, was worshipped by the Sumerians as the God of Shepherds and the consort of Inanna the Goddess of Lust and War. One could speculate that there was a Sumerian King Dumuzid that ruled before the Flood but it’s hard to imagine him ruling for 36000 years.

The first Sumerian King confirmed in the archaeological record is En-men-barage-si. He is listed as the 21st king after the Flood and ruling for 900 years. Archaeology dates him to sometime around 2700 BC which would allow some 200 years for the 20 Kings listed after the Flood until his rule. He was the King of Kish just as the King List states. The ‘En’ and ‘Men’ in his name are honorifics meaning Lord and Crown respectively so his name alone is Baragesi. Also in the archeological record is his son Aga. Their entry from the King’s List:

| En-men-barage-si, who made the land of Elam submit, became king; he ruled for 900 years. Aga, the son of En-men-barage-si, ruled for 625 years. 1525 are the years of the dynasty of En-men-barage-si. |

The date of Enmenbaragesi’s reign, 2700 BC, is interesting because excavations in the Sumerian city of Ur uncovered a necropolis of over 2000 graves some of which are dated to the same time period.

Royal Cemetery of Ur

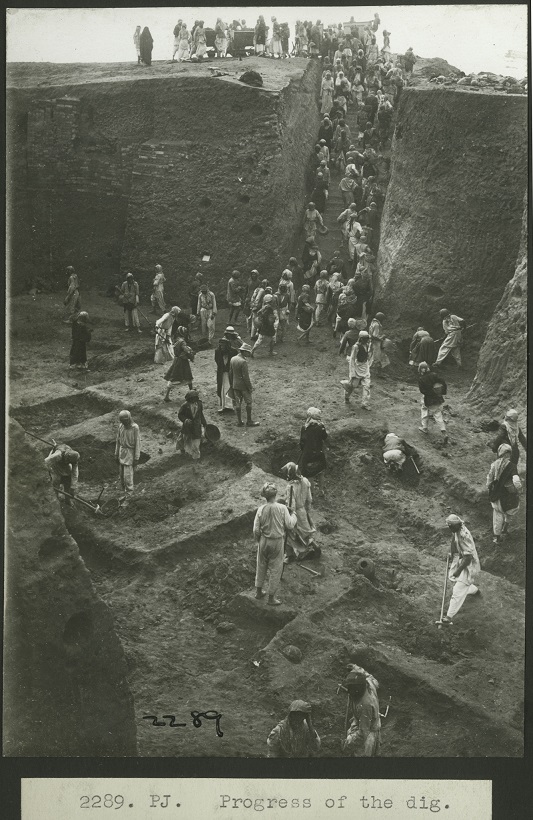

British archaeologist Charles Woolley begin excavations at the ancient Sumerian city-state of Ur in 1922, the same year that King Tutankhamun’s tomb was discovered in Egypt.

King Tut was a minor pharaoh in Egypt’s 18th Dynasty who apparently died unexpectedly since his tomb is small and unassuming. King Tut was the son of Akhenaten the Heretic Pharaoh and he was the product of inbreeding – DNA tests revealed that Tutankhamun’s parents were brother and sister, also his wife was his half-sister.

Tall but physically frail he had a clubbed left foot which was broken and infected at the time of his death; he became pharaoh in 1332 BC when only 9 years old and reigned but for 10 years. However when his un-looted tomb was discovered he became the most famous Pharaoh of all time. The tomb’s antechambers were packed to the ceiling with more than 5,000 artifacts, including furniture, chariots, clothes, weapons and 130 of King Tut’s walking sticks. Perhaps the most magnificent artifact in all of history is his 24 pound gold death mask.

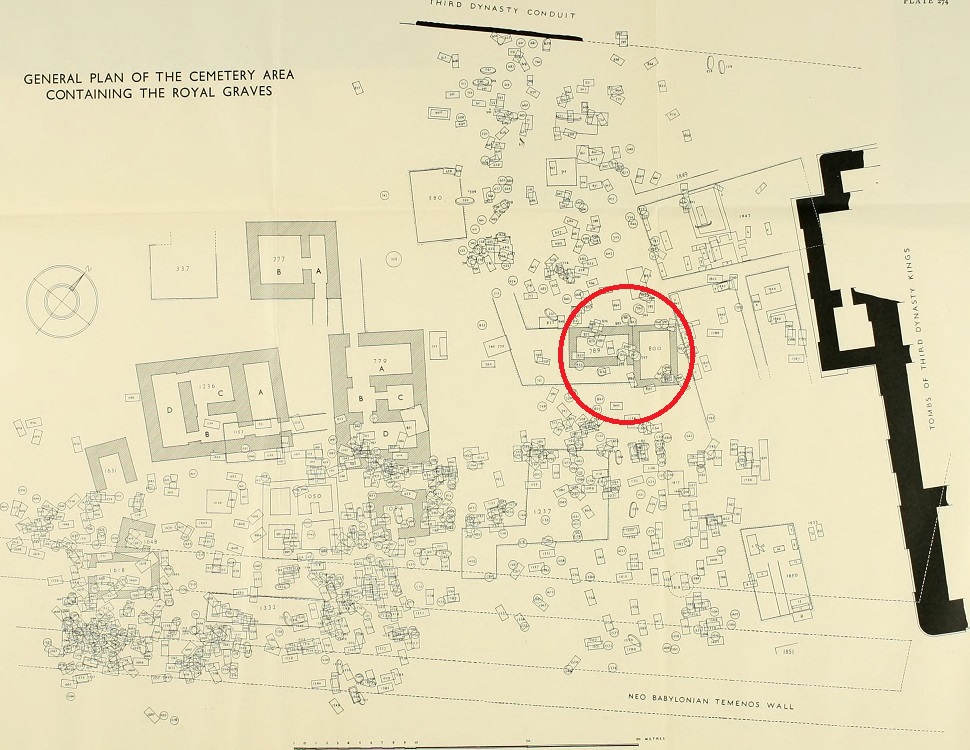

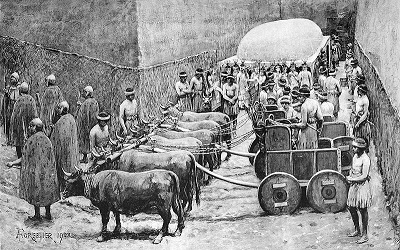

Woolley excavated for 12 consecutive seasons in Ur. He uncovered an ancient necropolis (graveyard) consisting of over 2000 burials a number of which he deemed ‘Royal’ due to their construction and grave goods. These Royal graves date to 2600-2300 BC during the Early Dynastic Period. This was a massive complex excavation:

Just like King Tutankhamun’s tomb, a number of Ur tombs were un-looted. Adding these Ur artifacts alongside the thousands of cuneiform tablets we have gives us detailed insight as the the wealth and majesty of the Early Dynastic Period.

One unexpected and especially grisly discovery was human sacrifice. A number of these tombs contained what Woolley called ‘death pits’ – a chamber separate from the tomb chamber which contained dozens of bodies of servants who likely died during a burial ceremony. Throughout Sumerian history there are no tablets which describe burial ceremonies and no indications of human sacrifice. Some Sumerian Kings were deified after their death and some even claimed to be God while alive – perhaps this is their rational for sacrificing attendants; so that they could continue to serve after death.

The “King’s grave” (PG 789) and the adjoining grave for Queen Pu-Abi (PG 800) serve as a good illustration. Both had a tomb chamber constructed of mud bricks which contained the royal body along with several personal attendants and elaborate grave goods. Outside the tomb chamber was a larger room – the ‘death pit’ – which contained dozens of sacrificed attendants.

The King’s tomb chamber had been looted so we do not know the King’s name but his ‘death pit’ was intact. Both of Queen Pu-Abi’s chambers were un-looted.

The above illustration shows the location of the attendants in PG 789, presumably during a religious ceremony after the King’s body had been interned in the tomb chamber (the white coffin like structure at the top of the graphic) and before the attendants committed mass suicide. Note the reed mats covering the walls; after the mass suicide the bodies and artifacts were covered with reed mats and the vertical pit was filled in with dirt. As a result of the weight of the soil and thousands of years many of the articles were crushed so some of the artifacts below are modern day reconstructions of the original artifact.

The King’s Grave was the earlier gave. When Queen Pu’Abi died, maybe some 20 years later, the Sumerians dug down to the Kings Grave and constructed Queen Pu’abi’s death pit directly above the King’s burial. But Pu’Abi’s tomb chamber was deeper than her death pit, it was placed beside the King’s tomb chamber at the same elevation as the King’s tomb chamber. While this is a clear indication that the Queen was in some way connected to the King we know from Pu-Abi’s cylinder seal that she ruled as Queen without a King. I think it is most likely that the unknown King was Pu-Abi’s father who she inherited the throne from; it’s unfortunate we don’t know his name. There is no record of Queen Pu-Abi other than her magnificent grave goods.

Private Grave 789 (PG-789)

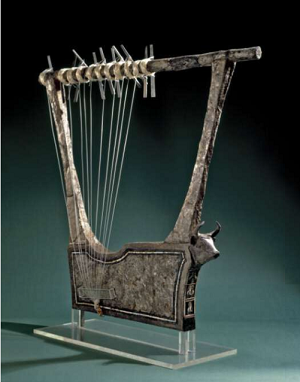

Woolley called PG-789 the ‘King’s Grave’ because of its elaborate death pit that included many weapons. The death pit contained the remains of more than 60 people, six of whom wore helmets and stood at the entrance as if to guard it. Their spears had a bull’s leg inscribed upon them which was likely the emblem of the King’s personal guards. The wood on this lyre was completely decomposed; hot wax was poured in the ground to pick up the imprint of the wood which allow a modern reconstruction. The face, ears, and horns of the bull’s head are made from separate pieces of gold. The beard, hair, horn tips, eye rims, and eye irises are made from lapis lazuli and the whites of the eyes are made from shell.

View high resolution images of this lyre at Penn Museum

There were four more lyres found throughout the excavations.

You can view a detailed review of these lyres here.

Private Grave (PG 800)

Queen Pu-Abi’s tomb chamber and death pit were both unlooted. There were 52 dead ‘attendants,’ 3 within the tomb chamber with Pu-abi’s body and the rest in the death chamber including 5 soldiers guarding the entrance. We know little about Queen Pu-Abi’s life or reign. We do know that she died when she was about 40 years old and was about 5 foot tall. She was likely not Sumerian since her name means “word of the Father” in Akkadian. But finding her tomb un-looted gives us insight as to what ‘opulence’ looked like in 2600 BC.

Her Royal sledge-chariot, drawn by two asses, was made of wood and was badly decomposed. Wheeled chariots were in use at the time (about 2600 BC) so finding the Queen using a sledge indicates the wheeled chariots weren’t really very practical. Most of Sumer was sand and the four heavy solid wheels made pulling the chariot through the sand a most difficult task even for a team of asses or oxen.

The walls of Pu-Abi’s tomb chamber was constructed of limestone and the domed roof was made of kiln-fired mud bricks. Yes, the Sumerians used arches in their architecture! The arching roof had collapsed over the span of thousands of years so even though the tomb was unlooted excavations were difficult.

The only artifacts which survived the ages nearly intact were objects made of silver or gold. Never the less, modern reconstructions show how a Queen of Ur was attired in 2600 BC. The whole of the upper part of the queen’s body was covered with beads of gold, silver, lapis-lazuli, carnelian, and agate because the material holding them in strings had decomposed. Her jewelry weighted 14 pounds! While many of the female ‘attendants’ were wearing head-dresses and jewelry the regalia worn by the queen was by far a more splendid and elaborate version.

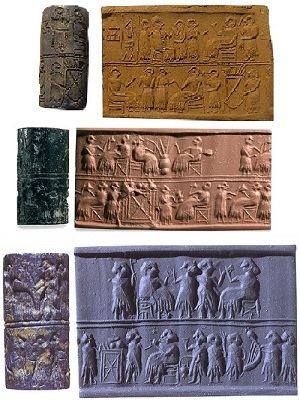

She was identified by 3 cylinder seals which had been pinned to her clothing on her chest. The 3 seals were probably made during different periods of her life. The bottom seal shows her as queen while the center seal shows her enjoying beer! The Sumerian’s favorite beverage was beer and they drank it out of huge pots through silver straws.

|

|

|

| Queen Pu’Abi’s Headdress For Additional Images |

Queen Pu-Abi’s 3 lapis lazuli cylinder seals | Sacrificed attendant’s headdress |

|

|

|

| Golden Shell holding eye shadow | The world’s oldest board game | Queen Pu’Abi wore 10 Rings |

Besides The King’s Grave (PG 789) and Queen Pu-Abi’s grave (PG 800) there were a number of graves which are called ‘Royal’ because of size of the grave, the grave goods recovered or sacrificed attendants. There were three parties excavating at the Royal Cemetery of Ur; the government of Iraq, the British Museum and University of Pennsylvania. The agreement was that Iraq would claim half the artifacts recovered and the remainder would be divided between U of Penn and the British Museum. All the below objects are displayed at one of the three museums:

The British Museum has the best online collection available here (click ‘Related Objects’)

The Penn Museum has an online Near East & Babylonian Collection which includes Sumer

|

|

|

| Ceremonial Dagger | Cooper War Ax | Golden Helmet of Meskalamdug |

|

|

|

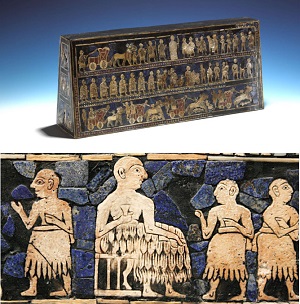

| Standard of Ur | Ram in the Thicket | Silver lyre |

|

|

|

| Gold and carnelian beads | Shell inlay of two standing goats | Etched carnelian beads |